Function Calls

So far, we have been focused on programming constructs that occur within functions. Let's turn our attention to what happens when one function calls another, or when a function completes execution and returns control to the function that called it. This video illustrates some of those concerns:

The Stack Frame

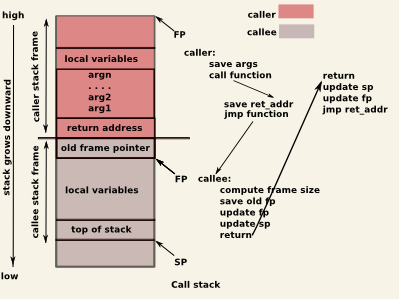

Before we can get into more detail about what happens when functions are called, we first need to introduce the concepts of call stack and stack frame.

The call stack is a data structure used by programming languages to keep track of function calls. It operates on a last-in, first-out (LIFO) principle, meaning the last function that gets called is the first to be completed and removed from the stack.

Each time a function is called, a stack frame is pushed onto the call stack. A stack frame typically includes:

- Return address: Where the program should continue after the function ends.

- Parameters: The arguments passed to the function.

- Local variables: Variables that are only accessible within the function.

- Saved registers: The state of the CPU registers that need to be restored when the function call is complete.

The stack frame ensures that each function call has its own separate space in memory for variables and state, allowing for recursion and reentrant functions.

Once again, when a function is called, a new stack frame is added to the stack and when the function returns, its stack frame is popped off the stack allowing control to be transferred back to the calling function.

Watch this video, which illustrates these concepts:

Now, study the following diagram from https://ocw.cs.pub.ro/courses/cns/labs/lab-03 and ensure you are familiar with the different elements in the stack and stack frames.

Before continuing, read the following two articles:

Calling Functions

In C programming, when you call a function, the process is abstracted from you, but understanding what happens at the assembly level can be quite insightful. As we have done throughout this module, we will start with a simple example in C, study the corresponding assembly code, and then gradually increase the complexity.

So, let's look at this example of a function calling another function. Note that there are no arguments, nor do either of the functions return a value.

C code:

void addNumbers() {

int sum = 10 + 32; // The sum is computed but not used since we don't return anything.

}

void myFunction() {

addNumbers(); // Call addNumbers, but there's no return value to handle.

}

Equivalent Assembly (x86):

.globl addNumbers

addNumbers:

# Code to compute sum would go here, but since we don't use the result,

# we can omit it for a void function.

ret # Return from addNumbers.

.globl myFunction

myFunction:

call addNumbers # Call the addNumbers function.

# No need to handle a return value since addNumbers is void.

ret # Return from myFunction.

The call instruction is used in assembly language to invoke functions. When a call instruction is executed, the CPU does two main things:

- Pushes the address of the next instruction (return address) onto the stack so that the program knows where to return after the function execution.

- Jumps to the target function's starting address to begin execution.

The ret instruction is used in assembly language to return from a procedure or function. When ret is executed, it performs the following actions:

-

Pops the top value from the stack into the instruction pointer register (

EIPon x86 architectures). This value is typically the return address, which was pushed onto the stack by thecallinstruction when the function was initially called. -

Transfers control to the instruction located at the return address, effectively resuming execution at the point immediately after where the function was called.

In summary, the ret instruction is responsible for cleaning up after a function call by restoring the instruction pointer to its previous state, allowing the program to continue executing from where it left off before the function call.

That a simple example. In the next section, we will dive into more complex examples!

Check Your Understanding: For the above example, draw on paper how the stack changes with each instruction execution based on the descriptions of what the instructions do.