Context Switching

In order for the operating system to have more than one thread underway on a processor, the system needs to have some mechanism for switching attention between threads. In particular, there needs to be some way to leave off from in the middle of a thread’s sequence of instructions, work for a while on other threads, and then pick back up in the original thread right where it left off. In order to explain this context switching as simply as possible, I will initially assume that each thread is executing code that contains, every once in a while, explicit instructions to temporarily switch to another thread. Once you understand this mechanism, I can then build on it for the more realistic case where the thread contains no explicit thread-switching points, but rather is automatically interrupted for thread switches.

Thread switching is often called context switching, because it switches from the execution context of one thread to that of another thread. Many authors, however, use the phrase context switching differently, to refer to switching processes with their protection contexts. If the distinction matters, the clearest choice is to avoid the ambiguous term context switching and use the more specific thread switching or process switching

Example

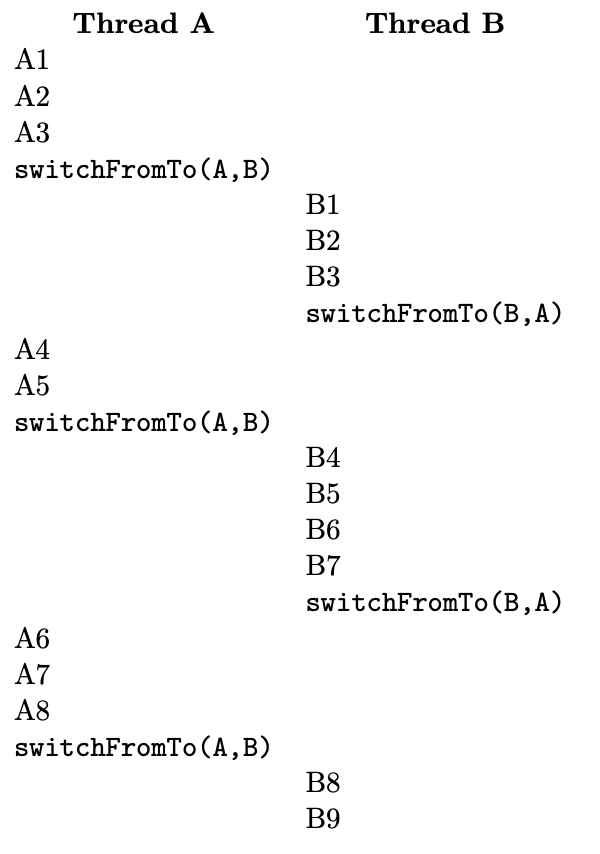

Suppose we have two threads, A and B, and we use A1, A2, A3, and so forth as names for the instruction execution steps

that constitute A, and similarly for B. In this case, one possible execution sequence might be as shown below.

As I will explain subsequently, when thread A executes switchFromTo(A, B) the computer starts executing instructions from

thread B. In a more realistic example, there might be more than two threads, and each might run for many more steps

(both between switches and overall), with only occasionally a new thread starting or an existing thread exiting.

Our goal is that the steps of each thread form a coherent execution sequence. That is, from the perspective of thread A, its execution should not be much different from one in which A1 through A8 occurred consecutively, without interruption, and similarly for thread B’s steps B1 through B9. Suppose, for example, steps A1 and A2 load two values from memory into registers, A3 adds them, placing the sum in a register, and A4 doubles that register’s contents, so as to get twice the sum. In this case, we want to make sure that A4 really does double the sum computed by A1 through A3, rather than doubling some other value that thread B’s steps B1 through B3 happen to store in the same register. Thus, we can see that switching threads cannot simply be a matter of a jump instruction transferring control to the appropriate instruction in the other thread. At a minimum, we will also have to save registers into memory and restore them from there, so that when a thread resumes execution, its own values will be back in the registers.

Basic Case

In order to focus on the essentials, let’s put aside the issue of how threads start and exit. Instead, let’s focus just on the normal case where one thread in progress puts itself on hold and switches to another thread where that other thread last left off, such as the switch from A5 to B4 in the preceding example. To support switching threads, the operating system will need to keep information about each thread, such as at what point that thread should resume execution. If this information is stored in a block of memory for each thread, then we can use the addresses of those memory areas to refer to the threads. The block of memory containing information about a thread is called a thread control block or task control block (TCB). Thus, another way of saying that we use the addresses of these blocks is to say that we use pointers to thread control blocks to refer to threads.

Our fundamental thread-switching mechanism will be the switchFromTo procedure, which takes two of these thread control

block pointers as parameters: one specifying the thread that is being switched out of, and one specifying the next

thread, which is being switched into. In our running example, A and B are pointer variables pointing to the two threads’

control blocks, which we use alternately in the roles of outgoing thread and next thread. For example, the program for

thread A contains code after instruction A5 to switch from A to B, and the program for thread B contains code after

instruction B3 to switch from B to A. Of course, this assumes that each thread knows both its own identity and the

identity of the thread to switch to. Later, we will see how this unrealistic assumption can be eliminated. For now,

though, let’s see how we could write the switchFromTo procedure so that switchFromTo(A, B) would save the current

execution status information into the structure pointed to by A, read back previously saved information from the

structure pointed to by B, and resume where thread B left off.

We already saw that the execution status information to save includes not only a position in the program, often called the program counter (PC) or instruction pointer (IP), but also the contents of registers. Another critical part of the execution status for programs compiled with most higher level language compilers is a portion of the memory used to store a stack, along with a stack pointer register that indicates the position in memory of the current top of the stack.

When a thread resumes execution, it must find the stack the way it left it. For example, suppose thread A pushes two items on the stack and then is put on hold for a while, during which thread B executes. When thread A resumes execution, it should find the two items it pushed at the top of the stack—even if thread B did some pushing of its own and has not yet gotten around to popping. We can arrange for this by giving each thread its own stack, setting aside a separate portion of memory for each of them. When thread A is executing, the stack pointer (or SP register) will be pointing somewhere within thread A’s stack area, indicating how much of that area is occupied at that time. Upon switching to thread B, we need to save away A’s stack pointer, just like other registers, and load in thread B’s stack pointer. That way, while thread B is executing, the stack pointer will move up and down within B’s stack area, in accordance with B’s own pushes and pops.

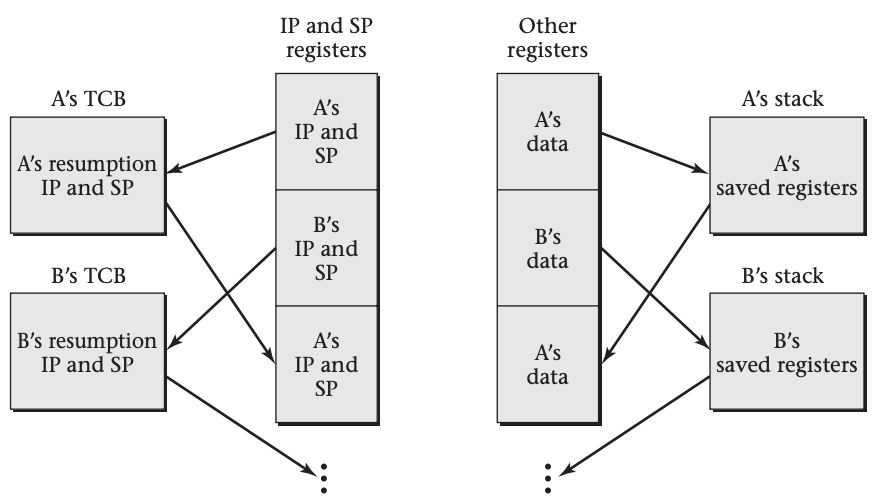

Having discovered this need to have separate stacks and switch stack pointers, we can simplify the saving of all other

registers by pushing them onto the stack before switching and popping them off the stack after switching, as shown in the figure above. We can use this approach to outline the code for switching from the outgoing thread to the next thread,

using outgoing and next as the two pointers to thread control blocks. (When switching from A to B, outgoing will be A

and next will be B. Later, when switching back from B to A, outgoing will be B and next will be A.) We will use

outgoing->SP and outgoing->IP to refer to two slots within the structure pointed to by outgoing, the slot used to save

the stack pointer and the one used to save the instruction pointer. With these assumptions, our code has the following

general form:

push each register on the (outgoing thread’s) stack

store the stack pointer into outgoing->SP

load the stack pointer from next->SP

store label L’s address into outgoing->IP

load in next->IP and jump to that address

L:

pop each register from the (resumed outgoing thread’s) stack

Note that the code before the label (L) is done at the time of switching away from the outgoing thread, whereas the code

after that label is done later, upon resuming execution when some other thread switches back to the original one.

This code not only stores the outgoing thread’s stack pointer away, but also restores the next thread’s stack pointer.

Later, the same code will be used to switch back. Therefore, we can count on the original thread’s stack pointer to have

been restored when control jumps to label L. Thus, when the registers are popped, they will be popped from the original

thread’s stack, matching the pushes at the beginning of the code.

Linux Example

We can see how this general pattern plays out in a real system, by looking at the thread-switching code from the Linux operating system for the x86 architecture.

This is real code extracted from an old version of the Linux kernel, though with some peripheral complications left

out. The stack pointer register is named %esp, and when this code starts running, the registers known as %ebx and %esi

contain the outgoing and next pointers, respectively. Each of those pointers is the address of a thread control block.

The location at offset 812 within the TCB contains the thread’s instruction pointer, and the location at offset 816

contains the thread’s stack pointer. (That is, these memory locations contain the instruction pointer and stack pointer

to use when resuming that thread’s execution.) The code surrounding the thread switch does not keep any important values

in most of the other registers; only the special flags register and the register named %ebp need to be saved and

restored. With that as background, here is the code, with explanatory comments:

pushfl # pushes the flags on outgoing’s stack

pushl %ebp # pushes %ebp on outgoing’s stack

movl %esp,816(%ebx) # stores outgoing’s stack pointer

movl 816(%esi),%esp # loads next’s stack pointer

movl $1f,812(%ebx) # stores label 1’s address,

# where outgoing will resume

pushl 812(%esi) # pushes the instruction address

# where next resumes

ret # pops and jumps to that address

1: popl %ebp # upon later resuming outgoing,

# restores %ebp

popfl # and restores the flags

General Case

Having seen the core idea of how a processor is switched from running one thread to running another, we can now

eliminate the assumption that each thread switch contains the explicit names of the outgoing and next threads. That is,

we want to get away from having to name threads A and B in switchFromTo(A, B). It is easy enough to know which thread is

being switched away from, if we just keep track at all times of the currently running thread, for example, by storing a

pointer to its control block in a global variable called current. That leaves the question of which thread is being

selected to run next. What we will do is have the operating system keep track of all the threads in some sort of data

structure, such as a list. There will be a procedure, chooseNextThread(), which consults that data structure and, using

some scheduling policy, decides which thread to run next. We won't dive into scheduling, so think of it as a box for now. Using this tool, one can write a procedure, yield(), which performs the following four steps:

outgoing = current;

next = chooseNextThread();

current = next; // so the global variable will be right

switchFromTo(outgoing, next);

Now, every time a thread decides it wants to take a break and let other threads run for a while, it can just invoke

yield(). This is essentially the approach taken by real systems, such as Linux. One complication in the

multiprocessor systems is that the current thread needs to be recorded on a per-processor basis.

Preemptive Multitasking

At this point, I have explained thread switching well enough for systems that employ cooperative multitasking, that is, where each thread’s program contains explicit code at each point where a thread switch should occur. However, more realistic operating systems use what is called preemptive multitasking, in which the program’s code need not contain any thread switches, yet thread switches will none the less automatically be performed from time to time.

One reason to prefer preemptive multitasking is because it means that buggy code in one thread cannot hold all others up. Consider, for example, a loop that is expected to iterate only a few times; it would seem safe, in a cooperative multitasking system, to put thread switches only before and after it, rather than also in the loop body. However, a bug could easily turn the loop into an infinite one, which would hog the processor forever. With preemptive multitasking, the thread may still run forever, but at least from time to time it will be put on hold and other threads allowed to progress.

Another reason to prefer preemptive multitasking is that it allows thread switches to be performed when they best achieve the goals of responsiveness and resource utilization. For example, the operating system can preempt a thread when input becomes available for a waiting thread or when a hardware device falls idle

Preemptive multitasking does not need any fundamentally different thread switching mechanism; it simply needs the addition of a hardware interrupt mechanism, which we will learn about next.